Most creative people (myself included) are quick to rail against the constraints of many assignments that land in our laps. “There’s no time.” “Budget’s too small.” “Not enough leeway.” [Insert your favourite obstacle here.] It’s in our nature. We hate to be fenced in. But if you open yourself up to the possibilities and learn to love the guardrails, great things can happen. Examples from other fields:

Music. Most artists tend to do their best work early in their careers. They’re lean. Hungry. They have something to prove. Perhaps most importantly, they don’t have the time or money to languish in the studio and engage in the endless rounds of navel-gazing that suck the life out of any project. The Beatles, The WHO and the Stones cut their early records in mere days on 4-track recorders. Just compare Metallica’s early LPs, all anger and vitriol, with the creatively constipated band bickering like an old married couple in the documentary Some Kind of Monster.

In fact, once they’ve made it, many artists often put themselves back into the box of ‘less’ in an effort to recapture the magic that made them great in the first place. Paul McCartney cut the 14 tracks on CHOBA B CCCP (Back In The USSR) in a day. It’s loose, raw and full of life, unlike so many of the bloated productions he and others were putting out back then.

Food In stark contrast to the over-processed garbage most Americans put into their mouths, Michael Pollen argues in favour of eating only foods that are produced with 5 ingredients or less. It’s all in how the chef uses the ingredients rather than how many there are.

Wine Vintners on all continents have embraced sustainability and cleaner methods in an attempt to produce more honest wines. Given the havoc that global warming is wrecking on producers’ microclimates, this is no small undertaking. But the results are often stunning, as I wrote in my wife’s food and travel blog.

Movies Woody Allen caps most of his film budgets at $6 million, a paltry sum by Hollywood standards, where the average movie can easily cost $40 to $100 million, not counting marketing. Why? Because even with his enviable track record, it’s the only way he can retain artistic control and feel good about the final product.

Marketing So back to my chosen profession. Make no mistake, I’m a strong advocate for having the time to think a project through. Time allows you to get smart on a subject. It lets you get obvious solutions out of the way. It lets you work on a problem and then come back to the project with fresh eyes. But given the pace most clients move at these days, we rarely get enough of it.

A decent budget is also tops on most creatives’ wish lists. It’s easier to get attention when you have the media spend to be seen everywhere. It’s a lot harder to stand out when you have a small box to play in and you’re forced to make the idea king. It’s also nice to be able to afford top tier photographers, directors, editors and other collaborators to bring your idea to life. Again, not always the case.

So here are a few examples of marketers that did a great job of delivering their messages in incredibly simple yet powerful ways, ones that break through despite the limitations of what they’re working with.

Oil of Olay No overpaid celebrity shills. No beautiful models. No quasi-scientific claims. Just two simple words on the page (“Tock. Tick.”) that communicate a powerful anti-aging message. It’s so good you gotta wonder if it was created just for an award show entry.

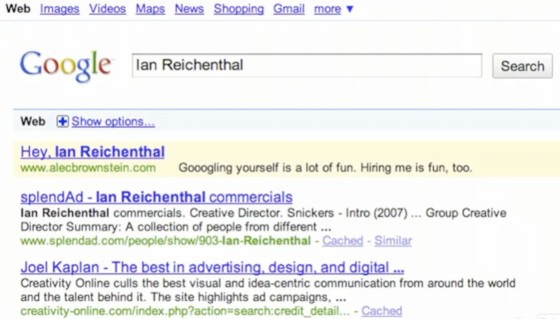

Job Hunt A fellow named Alec Brownstein was looking for a job but it was hard to get into the top shops. So, knowing what egomaniacs most creative directors are, he bought Google AdWords targeting his favourites that said, “Hey (name), Googling yourself is fun. Hiring me is fun too” with a link to his portfolio. Total cost? $6. He got a bunch of interviews, two offers, a job, and a few awards to boot. Nicely done.

Lego One of my favourite childhood toys (and my boys’ as well). Lego = imagination, a message that’s beautifully brought to life in these ads. Another advantage of being forced to strip things to the bone is that it allows the power of the idea to shine through. These ads could run in Mumbai or Mumford and be understood by parents and kids alike.

Allstate When the lights went out at the Super Bowl in New Orleans last year, Allstate pounced. ‘Mayhem’ took to social media, taking credit for the outage, and underscoring how quickly things can change. Brilliant, and cheap. And what client doesn’t love that?

The Economist This long running campaign from Abbott Mead Vickers in London (now adapted for the U.S. market) is instantly recognizable as The Economist. Simple. Powerful. Memorable. A single headline on red. That’s it.

Guinness A beer that claims to be ‘made of more’ celebrates two athletes that are also ‘made of more.’ One photo, type over picture, nice score and you’ve got a beautiful spot that’s more moving than most of the drivel that polluted the airwaves during the Super Bowl and the Olympics.

As my dad (an adman himself) and years of freelancing taught me, advertising is like sports: There’s no past, and no future. Nobody cares about the great idea you had last week or how many awards you won last year. They don’t care what you’ll do next year. It’s all about the moment. It’s put up or shut up. Like being a designated hitter. Or a gunslinger. It can be a lot of pressure. But the more comfortable you are with the guardrails, the better you’ll perform within them.

Ironically, the key to doing good work under these circumstances may be in ignoring one of the lessons we’ve had drummed into us since childhood: “safety first.” We’ve been told over and over that the guardrails are there to keep us safe. And in much of life, they are. But as in any creative field, you can’t let them lull you into a false sense of security. Or to become an excuse for not trying hard enough. Because if you don’t find a way to be creative within them, your competitors surely will.